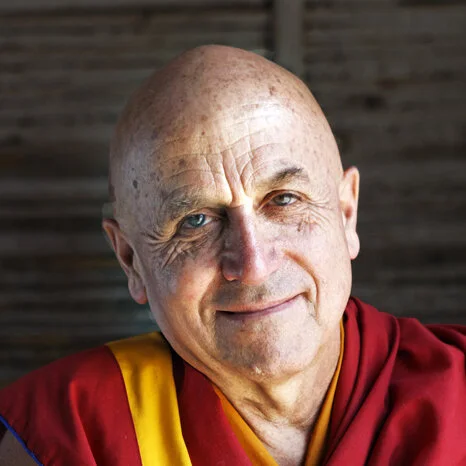

On October 24, 2017, Karma Lodro Gangtso of the Buddhist Monastic Intitiative had an opportunity to ask Matthieu Ricard a few questions on monastic life. Matthieu Ricard has been a monk for over 45 years, and is a celebrated humanitarian, author, photographer and translator. He was born in France.

Watch the interview, or read the transcript included below.

Full Transcript of Interview:

[Karma Lodro Gangtso:] Just to give you an idea of where I’m coming from, I’ve been ordained in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition for 2.5 years, and before that I lived in a Zen Monastery for 3 years. So I came from very structured community life in the zen tradition, and since I’ve been ordained as a Tibetan monastic I’ve realized there isn’t that structure really in place.

[Matthieu Ricard:] Because there aren’t that many monastic monasteries here in the west. Otherwise in the monasteries there are structures.

[KLG:] But in the west, like for me, I’m a student of Mingyur Rinpoche, and he’s advised me to move here. And I’m living alone. And talking with other monastics, it’s actually many, many monastics in the west living alone and trying to figure out how to do this.

[MR:] Because the sangha is supposed to be a community, to start with. It’s a challenge. Which is why maybe there are so many don’t stay monastics anymore.

[KLG:] So I think one of the questions is figuring out collectively how can we do this? What’s really important? And how can we bring monastic life to the west in a way that’s meeting the conditions and the culture of this place?

[MR:] Well since people are living alone anyway, and being monastics they’re not supposed to have many ties to this or that place or particular activity unless there’s a very specific need for one’s teacher. Indeed if they could regroup a bit, and have some kind of community, because they say when you have more than five that makes a sangha, so, even it’s small, that would be more community life, and that’s what the sangha is supposed to be. Why are they living alone? Because somehow, probably, it’s also material contingencies, they don’t have a place to stay that they can afford or doesn't cost them anything. But it’s possible if they were getting together they could find such a place where they could live together, and have community life. So, it would be desirable of course. Whether it’s feasible, and there is not too much asking considering the constraint of living in the west, material, financial and everything, I don’t know. Except, in the east, monastic would live alone it is really because they are in retreat somewhere, or very elderly monks they live with their family. Otherwise they live in a monastery, which is anywhere from 20 to 10,000. So, like Larung Gar there is 10,000 nuns they stay together, so that’s quite many. In Bhutan it is considered small when it is 150 nuns. Some have 60, some have 100. That’s a real community. In Tibet it’s like that. Bhutan also. Nepal also. Otherwise the alternative is wandering monks and nuns, which are like hermits, or retreatants, but besides that they’re not even supposed to… I mean, I myself don’t abide by this rule, it’s not the main rule that you break your vow, but you’re basically not supposed to spend more than three nights in a lay person’s home. But we are breaking that vow all the time. So, it’s a condition of the world. But I think there have been a few attempts to regroup communities. There was one in the south of France, I think it’s still going on. There was this thing at Gampo Abbey, I don’t know what’s happened. It would be desirable for sure. And maybe also better, when we get old we can look after each other, have the younger ones look after the elders. So ideally that’s what should be. So I think if we keep it as a goal, because it’s not going to happen just like that, we have to have a kind of vision to do that. So, especially if we could ask our teachers to help. Maybe when they have centers they could dedicate a piece of land, there are already some benefactors who do help for building temples and making statues, they could do something for having a basic, simple accommodations for this community. So if there is a sort of aim at doing that, I’m sure it can be accomplished. If everyone just fends for themselves, then it’s not going to happen by itself.

[KLG:] One thing I wanted to hear from you, in having these conversations I’ve talked to a lot of monastics who just struggle, they struggle with monastic life, they’re not sure if they want to do this anymore, I’ve had dear friend disrobe, and I want to hear from you, something positive about monastic life. What has been a joy for you?

[MR:] Well that’s also the strength of the community. If you are left on your own, then the environment, everything goes against that. Of course now people are more used to seeing monastics. They have seen His Holiness, they know about it. But in the past, they thought you are a strange sort of being, half human being because you cut yourself from so many things in life. So they didn’t have a positive opinion, in the west, of monastics. Usually “this guy’s not working, eating at the expense of others, so a sort of parasites.” While in the east so many people are so proud to help monastics survive. In Bhutan so many people told me, “you know, if you go on retreat I will provide all the food.” And then many of the donations that support monasteries is from locals. At least in our monastery, more than forty percent is the local community, they are very happy and honored to help the community. So there’s a whole culture. And also, because they live together, and according to one of the basic… the idea of monastic rules are like… you know… on the balcony you have a railing to prevent you from falling off. So there are safeguards to keep the vows, and that’s part of the community. But if you are left on your own, the whole world is geared against keeping these kind of vows. I mean advertisements, what you see on TV, and then people you meet they are themselves in worldly life, they make money, they have a family, they have companions and all that. So it’s like an upstream struggle, you don’t feel supported. While in the place where monastics are valued, where they can live their ideal, and there is a supportive community from outside and also a supportive community within the monastery itself. So then it’s definitely not the same sort of challenge. And also because it’s in the culture… First of all, many also young monastics leave when they become adults and before they take full vows. But the fact that they start quite early, it may seem funny for westerners that at ten years old you go as a novice to the monastery. But many many wants to do that, even children, they’re not just thrown by their parents but they want to do that rather than go to school. But more than half they leave before 20 years old, so they make up their minds before they’re adult life, before engaging in a profession and all that. So those who stay, they are much more likely to stay. Although some also leave. And there’s quite a few that leave. We have plenty of monks now who live in New York who are washing dishes or driving cars. So it’s not exceptional. And the former 16th Karmapa used to say that “if one out of ten become really good that’s quite nice.” So, like that. So I think, in the west, normally people are more advanced in age when they become monks, either in their 20s or 30s or more, so then they should think carefully, because you don’t have to be a monk to practice the path, or a nun. So there is reasons you can do that, it’s a kind of freedom from worldly affairs and worldy preoccupations. If you see that as a freedom then you’re more likely to remain. If you see that as a deprivation of something else then you not last very long. If you think that you are fettering yourself, diminishing yourself, then it’s not healthy. If you think, “wow, I’m a bird flying out the cage!” then you are more likely… if you keep on appreciating that freedom, that now nothing but the dharma matters to you. If that, you appreciate that, then why should you change and go back to these worldly activities, preoccupations, ups and downs, and lots of torments, unnecessary. So, if you don’t appreciate the freedom that it gives, the opportunity that it gives, then of course this will not last. Simply you did not recognize or didn’t appreciate or you were tempted by something else. So I think also making up one’s mind clearly before is a good thing, you should not rush certainly. At the same time the Buddha said that you take robes for even one day, wearing the monastic robes is like the victory banners of the Buddha’s teaching, so it’s immense merit. So in Thailand they have temporary vows, which probably might be an interesting formula for the west from Theravada, because then when they don't feel they are breaking something they just take the vows for some time. Tibetan Buddhism is of course is not like that, there’s no time limitation, so then you should better think carefully, you know, nobody forces you to become a monk, so, if you do it, just make sure that you feel it as a very strong positive liberating steps, and not because you have some problems that you want to get rid of it, and then you regret it because you feel caught into something. And also if you give it up, then what, you know, you have been doing it for a while, and better then playing poker.

[KLG:] You’ve already covered a lot of my questions, but one thing you brought up is this idea of being a parasite. And this comes up for me in my family, people really not supporting what I’m doing and thinking you know..

[MR:] My mom who’s a nun says that the western civilization is centrifuge, consumption, you go and buy things and gather them towards you. It’s always like that, getting things, getting things. And if you don’t get things then you’re a failure. Eastern culture are the opposite, it’s the opposite, things spin towards outside. In the west you bring things to you, increasing your wealth, bringing things to you. In the east it’s going like that [hands gesture outward]. I know an old nun, the moment she gets some money she says, “oh, what am I going to do? Offer lamps? Offer to the lama?” It’s an offering civilization. And that’s why it’s not a problem. Because people feel greatly honored to offer to monastics. Except maybe if you’ve been brainwashed, by new sort of fashion people. But everywhere they think it’s very great merit. And it’s not like they have been old fashioned brainwashed. They really think it. And some of them say, “we can’t do that ourselves, we don’t have the determination, and we already have five kids, but, it’s wonderful you are doing it, we are supporting you…” And even the monks who leave the monastery, usually because they leave on good terms, even if they are in New York they keep supporting the monastery because they feel that it is a good thing to do. And it’s a tradition. In China always kings were patroning monasteries. So in Buddhist country like Bhutan the community is most happy to support, it’s very different, and monks are very much respected. Not seen as… Well here of course it’s not our culture. That’s why His Holiness Dalai Lama said maybe better to keep your own tradition, except a few exceptions where you are really convinced that Buddhism is what fits or suits you, then you can do. But he said it’s always a little bit between two chairs. That’s why I live personally in the east, but not everyone can do. Because there it’s no problem.

[KLG:] One of the questions that comes up with some of the monastics I’ve talked to is since we’re in this culture, because of all this deep rooted psychology we have about bringing in and supporting ourselves, should monastics just do that, work and support ourselves or is it important to keep this integrity of…

[MR:] Well in some way you could, if really you are convinced that the monastic path is the right path for you, and it’s a virtuous path, and it’s the only way to work… I know of two brothers who are monks, ordained by Trulshik Rinpoche, who was really strict about the vinaya, and they remained monks for 30 years. They lived together in a small flat, they worked together in factories. They remained monks until the end of their lives. And they were very pure monks. But in the daytime they worked in the factory. And every two years they would come to Nepal and meet Trulshik Rinpoche and make some offerings. So… it was kind of nice to see them coming home and putting back their dress and doing practice. So it works well. I think the reason why we generally don’t encourage that is that people can’t, do not keep that. If they really do that, sort of anonymously being a monk at home, but being really pure monks or nuns, then it would be fine. But the problem is by doing that usually they veer away. So that’s the reason why working in a normal environment and being a monk or nun is not easy because you get sidetracked, and usually fall into not being a monk or nun anymore. But if you really abide by the precepts…. Normally you should not dress as a layman, but let’s admit that it’s okay if you really keep the spirit, but it’s really challenging. You really have to have a strong stability and confidence, and be absolutely clear in your mind. Then I guess it’s okay. I mean Trulshik Rinpoche would definitely have told them something if he thought it was improper. So.. and they were very nice, I don’t know what happens if they are still alive, but..

[KLG:] So, what does it mean to keep the spirit, to you, of being a monastic in your heart?

[MR:] Well you actually went from home to homelessness, so it means you observe the monastic vows. There are quite many, many enough, that you know what it is. But the spirit means to be really keen in observing the vows. So that’s the spirit. The monks is about behavior. Bodhichitta is about intention and pure vision is about vajrayana. But monastic rules is about conduct. It’s nothing… I mean of course the spirit of renunciation, but basically it’s observing a conduct, with the joy of doing so, that’s the motivation, and seeing the benefit of it. But it’s basically about being happy to observe the rules. If you are happy to observe the rules then it would be fine. But that’s the spirit of monastic vows. It’s not about bodhisattva ideal, or vajrayana seeing all phenomena as pure, which is the mind. There it is to value, being eager, and joyful in keeping the discipline, and if you are not then it’s not going to last, of course why should it last, you cannot force yourself all life long. So unless you’re happy to do so it’s not going to work. And if you’re happy to do so it will work even if you go in the factory all day. Because if you are not interested in doing other things then is following the vows. So then you keep them. But it’s certainly more challenging for the mind to be willing to keep the vows if you are constantly being distracted by something else. You need a very steady mind. So those two brothers in Switzerland who were going to the factory for thirty years, they had an extremely steady mind. For them it was clear. They were a monk, they will stay a monk, and they didn’t even consider alternatives.

[KLG:] Thank you very much.